How do practitioners spot pseudoscience in Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)? With so much information on the web these days, it can be challenging. In today’s post, we will be delving into what pseudoscience is and how to identify it.

Pseudoscience:

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, pseudoscience is defined as “A pretend or spurious science; a collection related beliefs about the world mistakenly regarded as being based on scientific method or having the status that scientific truths now have.”

There is a continuum, between science and pseudoscience, on which various AAC assessment protocols, interventions, and strategies align. After all, hypotheses can’t be proven. However, in our efforts to provide evidence-based practice (EBP), we strive to utilize those techniques that fall closest to the science end of the range.

Red Flags:

There are several red flags professionals can look for that suggest claims lean towards pseudoscience. One helpful criterion is if an approach is disconnected from well-established science in the field (Finn, Bothe & Bramlett, 2005). We humans have a natural bias towards assuming that new things are better just because they are new. This is known as the novelty effect. However, if a technique revolutionizes or radically diverges from leading theories, then there is a good chance it lies towards pseudoscience end of the continuum.

More Warning Signs:

- New terms that sound scientific but aren’t;

- Information that is presented directly to the public without first going through the scrutiny of peer-review;

- Techniques that seem too good to be true;

- Anecdotal evidence, often testimonials, from others who seem motivated by a genuine desire to help others.

(Finn, Bothe & Bramlett, 2005)

Science:

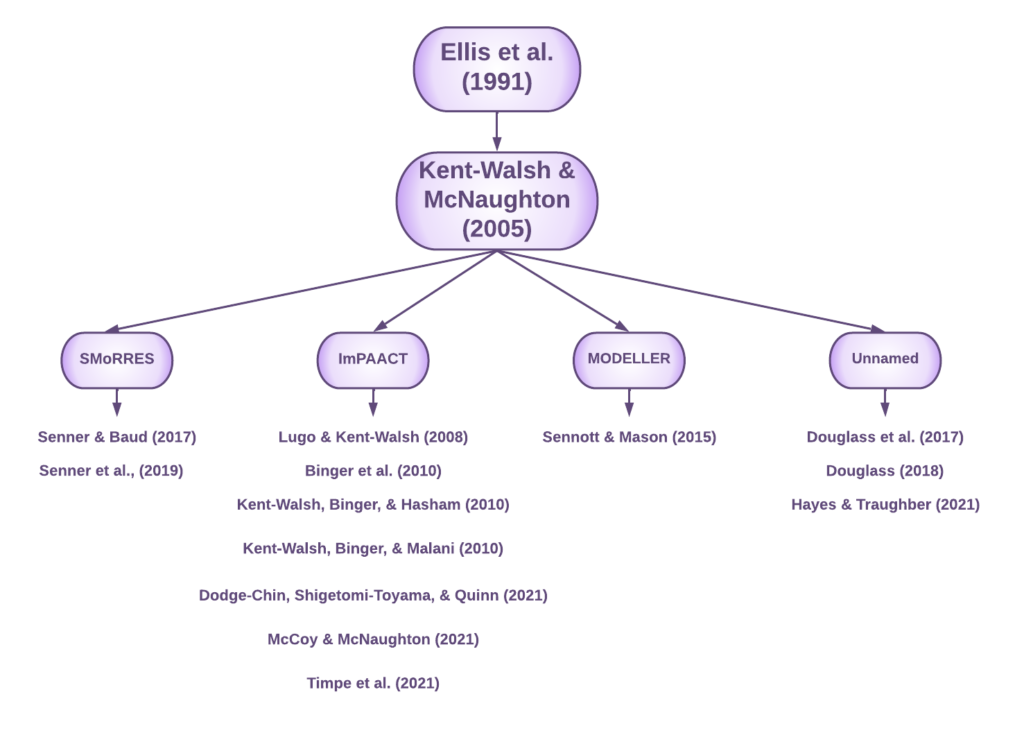

The scientific process ordinarily plods along incrementally, with each successive study slightly modifying or refining an established technique as the evidence base grows and we learn more (see figure 1).

The next time you’re scrolling through your news feed, exercise caution if you see any warning signs. If something sounds too good to be true, it probably is… and if it abandons connections to evidence-based paradigms, it may be pseudoscience.

References:

Finn, P., Bothe, A. K., & Bramlett, R. E. Science and Pseudoscience in Communication Disorders: Criteria and Applications. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14, 172-186. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2005/018)